Helene flooding strands hundreds of North Carolina residents as storm’s death toll reaches 95

‘We all really need help here’

Since Helene started swamping the region, it’s turned neighborhoods into lakes, lifted cars like toys, snapped trees like twigs and left businesses underwater. Piles of thick mud and floating debris blocked streets as torrential rains collapsed roadways and washed out bridges. It’s left hundreds of people in North Carolina stranded in homes, hospitals or transportation systems, awaiting rescue.

“The priority is getting people out,” North Carolina Gov. Cooper told CNN affiliate Spectrum News. “And getting supplies in.”

But officials face a major hurdle: “Everything is flooded. It is very difficult for them to see exactly what the problems are,” Cooper said.

On Friday, Stevie Hollander watched as floodwaters inundated his Asheville apartment complex, where he lives on the second floor with his sister and her fiancé.

“The water almost reached us but thankfully went down,” he told CNN. Most residents on the first floor left before their units were submerged, while other relocated to stay with residents on higher floors.

“We all really need help here. We need water, power of sorts, food, gas. Anything.” he said, “We just don’t really know what to do.”

Hollander and his family attempted to drive north Saturday, but road closures forced them to return to the apartment. The family only has four water bottles left and little nonperishable food, Hollander said.

In Black Mountain, North Carolina, Sofia Grace Kunst contended with another problem: a landslide she said tore through the window and wall of a dining hall where she was playing Uno with six friends while on a weeklong trip.

It was exactly 9:10 a.m. Friday when mud and debris shattered a window and poured into the room, she said.

“Landslide! Everybody run,” someone yelled.

“I see this giant wave of like mud and trees and rocks just coming towards us,” Kunst told CNN, estimating it was 5 or 6 feet high.

She ran into the main room of the dining hall, only to see the wall completely cave in. The group fled to the porch, where many of her peers were crying. Kunst sat in shock, barefoot.

It was only then she realized she still had her Uno cards in hand.

The group eventually trekked through muddy water, seeking refuge in a parking lot on higher ground. They were stranded there for some time, but eventually reached a shelter.

“That’s when it hit most people. There were a lot of tears,” Kunst said. “For me, it really didn’t hit me emotionally, but my body started reacting. I started shaking like crazy. I felt like I had to, like, scream or let off energy,” Kunst said.

Amid cleanup efforts, a Buncombe County resident told CNN she has no power, running water or cell phone reception.

Clutching firewood in her hands, Meredith Keisler, a school nurse, said: “We’re collecting wood because we have a grill to make fire, to cook food,” she said.

While Keisler says she considers herself lucky with resources at her home, she plans to work at a shelter to help others.

“It’s incredible — the destruction. It’s really sad,” she noted when asked about her surroundings.

In McDowell County, Krista Cortright said her boyfriend’s grandmother had no way of getting out of Black Mountain due to flooding. Cortright told CNN the couple had to get to her since she had limited supplies and she is diabetic.

It typically takes the couple 25 minutes to travel from Marion to the grandmother’s house. On Sunday, due to road closures, it took them 2.5 hours.

“Things are even more devastating in person,” Cortright said. “(Western North Carolina) is going to take a very long time to recover, but I am so grateful that we are here and doing OK. My heart is broken for our people here.”

CNN’s Sarah Dewberry, Rafael Romo, Jade Gordon, Ashley R. Williams, DJ Judd, Sunlen Serfaty, Lauren Mascarenhas, Eric Levenson, Isabel Rosales, Taylor Galgano, Sara Smart, Conor Powell, Caroll Alvarado, Caroline Jaime, Emma Tucker, Artemis Moshtaghian, Paradise Afshar and Raja Razek contributed to this report.

At least 87 people have been killed in six states since Helene swept through, including at least 30 in North Carolina.

Officials and residents assessed damage from Hurricane Helene in Woodlawn, N.C., and North Cove, N.C., on Sept. 28. (Video: Julia Wall/The Washington Post)

BLACK MOUNTAIN, N.C. — As skies cleared and at least some roads here became navigable again, Breanna Boaz had a plan for how she and her family were going to survive the aftermath of Helene: flee.

“I’m trying to find a way out of here,” said Boaz, 32, who has an 8-month-old daughter. Her mother is close by and would come with them. “As soon as I’m certain we can leave, we will leave.”

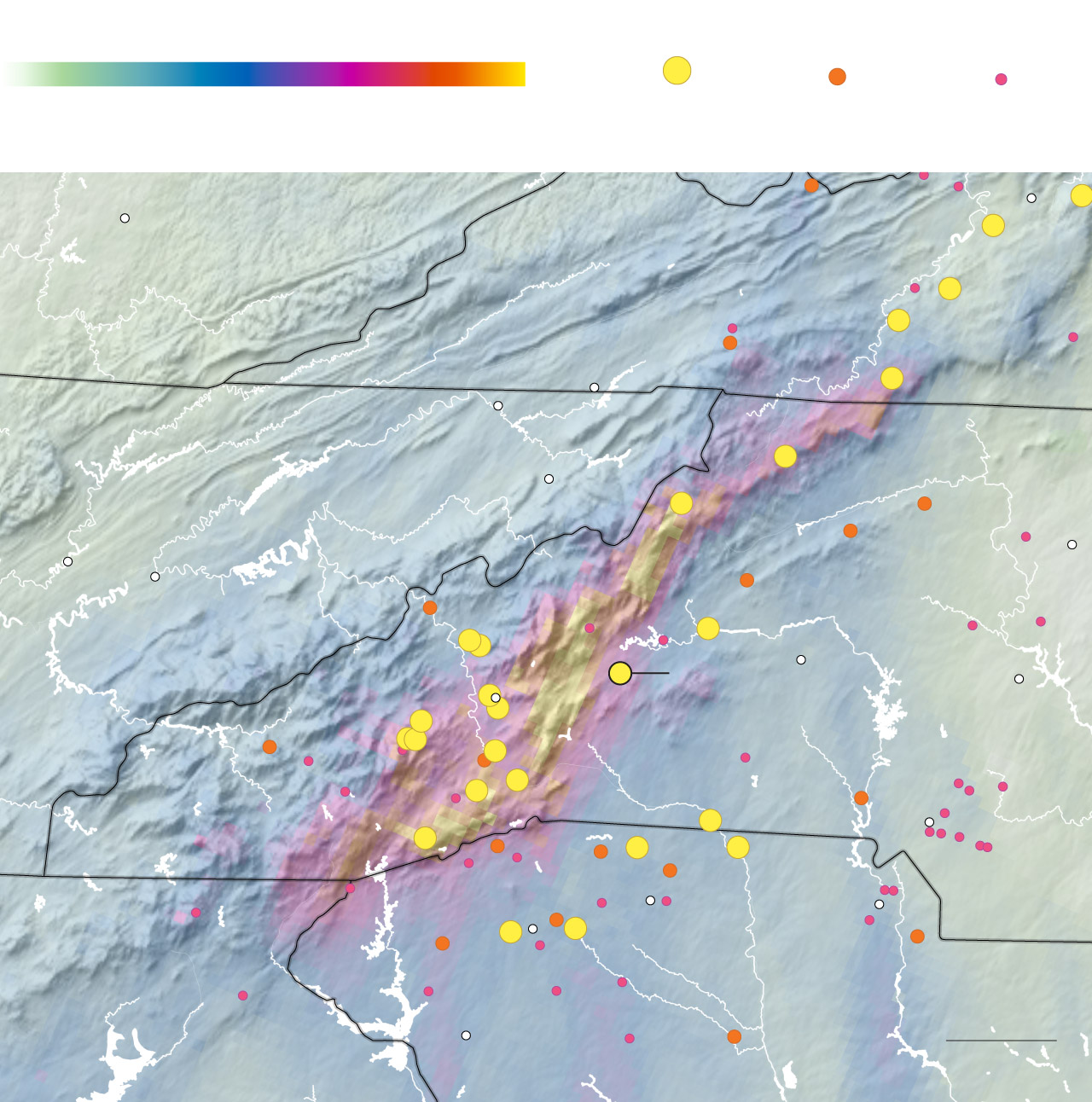

In small North Carolina mountain towns pummeled by Helene, which made landfall Thursday on Florida’s Gulf Coast as a Category 4 hurricane, reality is setting in for many people about how long they might be left isolated without running water, power, cell service and internet. The powerful storm unleashed torrential downpours, leading to catastrophic flooding that washed out roads, damaged water and power systems, left neighborhoods underwater, and claimed dozens of lives from Florida to the southern Appalachians.

In the days since the storm swept through, cellphone and internet signals in this region have been spotty — if working at all — making communication with the outside world a constant struggle. People shared posts on Facebook looking for friends and loved ones, or asking others to check on relatives. Major roads remained impassable in places, and few people had managed to make it to many of the smaller, winding ones that weave along the valleys and rivers of this region.

At least 87 people have been killed in six states. In North Carolina, at least 30 people have died. South Carolina reported at least 25 deaths; Georgia, 17 deaths; Florida, 11; Tennessee, 2; and Virginia, 2.

North Carolina’s Buncombe County, which includes Asheville, was working through hundreds of reports from people looking for loved ones, county manager Avril Pinder said in an afternoon briefing. Earlier, officials said there were more than 1,000, but hours later they had cleared reports to “well below 600.”

“We’re still conducting search operations and we know that those also may include recovery operations,” said Buncombe County Sheriff Quentin Miller.

Many elsewhere remain unaccounted as well. In Tennessee, for one, more than 150 people have been reported missing, Myron Hughes, a spokesman for the Tennessee Emergency Management Agency said during a Sunday news conference.

More than 300 roads remain closed in North Carolina, according to federal officials. That includes multiple stretches of Interstates 40 and 26, which are the main roadways for traveling in and out of Asheville.

Power was slowly being restored across affected states. More than 480,000 people remain without power in North Carolina as of Sunday afternoon. In South Carolina, more than 800,000 people still don’t have electricity.

Duke Energy said Sunday nearly all of its customers outside the western parts of the Carolinas should have power again before 11:59 p.m.

“Across the North Carolina mountains and Upstate of South Carolina, major challenges persist and are impeding our ability to assess damage and give estimates for when power is likely to be restored,” the power company wrote in a post on X.

“This is going to be a really complicated recovery,” FEMA Administrator Deanne Criswell said in an interview on CBS’s “Face the Nation.” Criswell visited Georgia on Sunday and said she will be on the ground in North Carolina on Monday.

Outside Asheville in Swannanoa, fire chief Anthony Penland said the main area of town is “completely devastated.” Part of Highway 70 that runs through Swannanoa is gone, Penland said.

Search-and-rescue crews have been deployed, but reaching affected areas has been challenging, Penland said. In places where crews have been able to enter, little is left.

“We have complete neighborhoods that are no longer there,” he said. “We’re just trying now to go to where these neighborhoods were and just try to do some sort of search-and-rescue in some of the houses that are still there.”

Access to critical resources, including water and food, also continues to remain limited across much of Buncombe County. County officials have been working to set up food and water distribution sites, but Pinder said Sunday none were open yet.

The county, she said, was told that there would be “several tractor-trailer loads of water” coming into the community. The delay, Pinder said, is probably due to storm-related road closures hindering the transport.

Pinder added that officials have been working with state emergency services, noting that state authorities are responsible for coordinating federal assistance.

Cooper said Sunday the state has already started airlifting supplies, including food and water, into the region.

“People are desperate for help, and we are pushing to get it to them,” Cooper said during a news conference.

“This is an unprecedented tragedy that requires an unprecedented response,” he added.

Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis (R) announced his state, also hit hard by Helene, would be sending emergency personnel and resources, including two CH-47 Chinook helicopters and crew, to North Carolina and Tennessee.

Biden administration officials said federal resources and personnel in western North Carolina have been in position for about a week, and President Joe Biden has been in contact with state and local leaders.

Jeremy Greenberg, director for the operations division in FEMA’s response directorate, said in an interview that the agency began working with meteorologists from the National Hurricane Center about a week ago and knew Helene would make immediate landfall in Florida but push into North Carolina and Georgia. The remote and mountainous region of western North Carolina has created especially challenging conditions for the federal response, officials said.

Greenberg said FEMA deployed an emergency assistance team and worked with North Carolina officials to understand how they wanted to handle the geography of the hardest-hit regions, adding that the government has over 500 search-and-rescue personnel working in addition to state rescuers.

In the meantime, local residents are banding together to help one another.

On Sunday afternoon along Highway 70, the road that connects Black Mountain to nearby Swannanoa, a line of hundreds of people snaked around the parking lot of the Pisgah Brewing Company, where a large handmade sign hung out front that read: “H2O.”

They carried five-gallon plastic containers and milk cartons and even orange Home Depot buckets. Each had come in search of water — one of the resources so desperately hard to find here in the wake of Helene. Some waited in line an hour and were barely halfway through.

Dave Quinn, the brewery’s owner, was sitting at the front of the line with several of his employees, still filling bottles six hours after he began for the day. He said the brewery always keeps two 4,000-gallon tanks of clean water in reserve — though he found himself wishing he would have filled more tanks before the storm.

What he had would probably be given away before day’s end.

“We’ll probably give 1,000 people water today, at least,” Quinn said. “I wish we could keep going nonstop.”

Almost two hours after his wait began, Frank Gentry of Swannanoa had almost reached the front of the line with his five-gallon containers. They weren’t even for him, but rather for elderly neighbors in the town who needed water and weren’t able to stand in line.

“There’s no drinking water. … You can’t cook,” Gentry, 38, said of the situation so many people here have found themselves in. “We’re so cut off and isolated.”

Days after the rain subsided in the Southern Appalachians, numerous flood alerts were still in effect because of continued runoff and swollen waterways. Multiple flash flood emergencies, the most dire flood alert, were in effect Sunday for numerous lakes along the Catawba River in western North Carolina because of both “catastrophic and historic inflows” and dam releases that could lead to “life-threatening” flooding downstream.

And there is concern about the possibility of more rain in the region.

The remnants of Helene, which drifted west into the Tennessee and Ohio valleys, are forecast to shift east through the Mid-Atlantic late Sunday into early next week.

That will bring some more showers to parts of the Southern Appalachians, though amounts are generally predicted to be light.

In the hardest-hit areas of western North Carolina, eastern Tennessee and southwest Virginia, amounts are predicted to be generally under an inch.

“This additional rainfall is not expected to exacerbate ongoing flooding but may lead to excessive runoff due to saturated soils,” said the National Weather Service office serving the western Carolinas.

At the West Asheville River Link Bridge on Saturday evening, overlooking the city’s funky, vibrant River Arts District, residents looked down over the river that had swallowed a city park, railroad tracks, nearby streets and numerous businesses. Even as the French Broad River had receded some in the past day, few had ever seen it this high in their lifetimes.

Mattresses, lumber and other debris floated down the river. A thick layer of mud coated nearby businesses, and several remained underwater.

Colton Dion, a 28-year-old artist whose nearby studio narrowly escaped the flooding, sat painting the swollen river in the evening light.

“I just wanted to document it,” he said. “It definitely marks an era here.”

Standing alone at a railing above the river, Israel Mayfield looked out over his hometown, marveling at how unrecognizable it was.

He pointed in the distance to a well-known music spot, the Guitar Bar, its structure nearly demolished even as the river still ran through it.

He recalled how there was a memorial service there once, after his father died.

Looking around, he spoke of the business owners he knew and wondered if they had flood insurance, if some of them would ever recover, if this creative and beloved corner of the mountains would emerge with its unique spirit and its economy intact.

“There’s just no telling,” he said, though he was holding out hope that the people who gave life to this neighborhood before might soon return.

“There’s a glass blower over there,” he said, “and there’s an iron worker down this way. And there’s a heck of a barbecue joint right over there.”

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(723x411:725x413)/Frank-Fritz-100224-43e6af9f1eed4fc6b8c825ee4b3d63e4.jpg?w=1200&resize=1200,0&ssl=1)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(599x0:601x2)/jack-wagner-michelle-wolf-wedding-tout-060325-fbc90e73fa6449058b91f22f998dcdda.jpg?w=1200&resize=1200,0&ssl=1)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(749x0:751x2)/princess-beatrice-princess-eugenie-prince-andrew-112524-f04c800ab0da4b0ab1f8429988ce5631.jpg?w=1200&resize=1200,0&ssl=1)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(749x0:751x2):format(webp)/Dog-missing-in-Colorados-mountains-for-43-days-reunited-with-owner-thanks-to-Summit-Lost-Pet-Rescue-022426-0ebb1d6502764f8eb20d846307727ad0.jpg?w=1200&resize=1200,0&ssl=1)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(754x379:756x381):format(webp)/chow-chow-bowling-green-subway-70ac9e829e20441a978d9f05a1085374.jpg?w=1200&resize=1200,0&ssl=1)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(725x300:727x302):format(webp)/Bridget-Garrison-dogs-tally-karma-01-021926-5f803803830d4771a5d48258b325f341.jpg?w=1200&resize=1200,0&ssl=1)