Aging Americans Face a ‘Silent Epidemic’ of Diabetes

Washington D.C. — Diabetes is rapidly becoming one of the most significant health threats to older adults in the United States, posing complex challenges that extend far beyond medical care and deeply impact their daily lives. According to health experts, the disease is quietly spreading within the population aged 60 and older, making them one of the most vulnerable groups.

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the American Diabetes Association reveal that nearly 30% of Americans aged 65 and older have diabetes. This figure is more than double the prevalence rate for individuals aged 45-64.

However, for older adults, diabetes is more than just a statistic. It’s a complex challenge that triggers dangerous complications and erodes their independence.

A Compounding Burden of Complications

Diabetes isn’t just about blood sugar. It’s the underlying cause of a range of chronic complications that are particularly severe in older adults. Diabetic neuropathy can lead to a loss of sensation in the feet, increasing the risk of falls and causing slow-healing sores that may necessitate amputation.

Furthermore, diabetes is closely linked to other serious conditions common in the elderly, including kidney failure, blindness, heart disease, and stroke. Many older adults find themselves managing multiple co-existing conditions, a situation known as “multimorbidity,” which makes treatment more complex and costly.

Daily Life is Profoundly Affected

Beyond the physical difficulties, diabetes places significant barriers on daily life. A strict dietary regimen can diminish the joy of eating and make it difficult to share meals with family and friends. Managing medications and checking blood sugar multiple times a day requires dexterity and a good memory, skills that not all older adults retain.

Diabetes has also been shown to increase the risk of cognitive decline and dementia, making it harder for individuals to care for themselves. Many older adults with diabetes gradually become dependent on caregivers, which can strip away their sense of autonomy. Moreover, the financial burden of medications and medical services can be a heavy stressor, especially for those on a fixed income.

Mark Johnson, a 75-year-old Arizona resident, shared: “This disease has completely changed my life. I’m constantly worried about my blood sugar levels, and the numbness in my hands and feet makes me unable to do simple things I used to enjoy.”

Comprehensive Support is Key

In the face of this “silent epidemic,” health professionals emphasize the importance of holistic care that includes medical, mental, and social support. Increasing education about healthy lifestyles, providing accessible primary care, and developing programs to support older adults are crucial steps to help them manage diabetes safely and maintain a high quality of life.

Diabetes in the elderly isn’t just an individual’s responsibility. It requires a collective effort from the community and the healthcare system to ensure that older adults can live a fulfilling and independent life, despite the challenges this disease presents.

After 60 Years, Diabetes Drug Found to Unexpectedly Impact The Brain

Metformin has been prescribed to people with type 2 diabetes to manage blood sugar for more than 60 years, but scientists haven’t been exactly sure how it works. A new study suggests it works directly in the brain, which could lead to new types of treatment.

The study, carried out by researchers from the Baylor College of Medicine in the US, identifies a brain pathway that the drug seems to work through, in addition to the effects it has on biological processes in other areas of the body.

“It’s been widely accepted that metformin lowers blood glucose primarily by reducing glucose output in the liver,” says Makoto Fukuda, a pathophysiologist at Baylor. “Other studies have found that it acts through the gut.”

“We looked into the brain as it is widely recognized as a key regulator of whole-body glucose metabolism. We investigated whether and how the brain contributes to the anti-diabetic effects of metformin.”

Previous work by some of the same researchers had identified a protein in the brain called Rap1 as having an impact on glucose metabolism, particularly in a part of the brain called the ventromedial hypothalamus or (VMH).

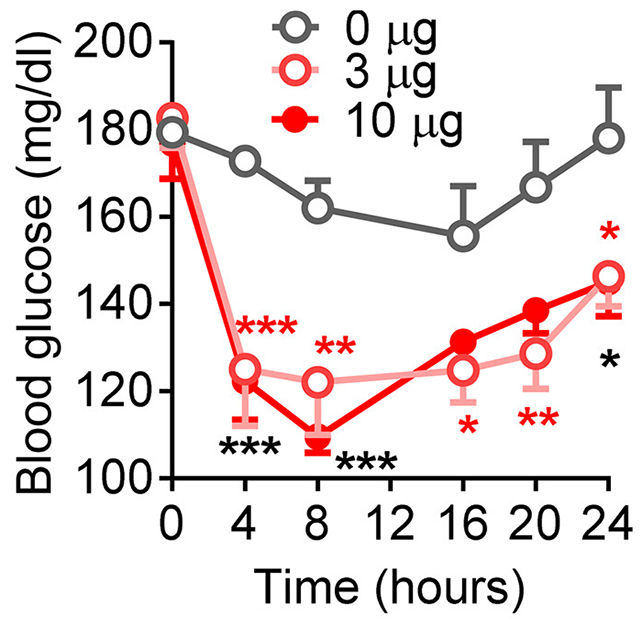

In the new study, tests on mice showed metformin traveling to the VMH, where it helps tackle type 2 diabetes by essentially turning off Rap1.

When the researchers bred mice without Rap1, metformin then had no impact on a diabetes-like condition – even though other drugs did. It’s strong evidence that metformin works in the brain, through a different mechanism than other drugs.

The team was also able to take a close look at the specific neurons metformin was changing activity in. Further down the line, that could lead to more targeted treatments that take aim at these neurons specifically.

“We also investigated which cells in the VMH were involved in mediating metformin’s effects,” says Fukuda.

“We found that SF1 neurons are activated when metformin is introduced into the brain, suggesting they’re directly involved in the drug’s action.”

Metformin is safe, long-lasting, and relatively affordable. It works by reducing the glucose produced by the liver and increasing how efficiently the body uses insulin, helping to manage the symptoms of type 2 diabetes.

Now we know it very probably works through the brain, as well as the liver and the gut. Clearly, this needs to be shown in human studies as well, but once that’s established, we might be able to find ways to boost metformin’s effects and make it more potent.

This also ties into other interesting studies that have found the same drug can slow brain aging and improve lifespan. With a better understanding of how metformin works, we may see it used for a broader range of purposes in the future.

“This discovery changes how we think about metformin,” says Fukuda. “It’s not just working in the liver or the gut, it’s also acting in the brain.”

“We found that while the liver and intestines need high concentrations of the drug to respond, the brain reacts to much lower levels.”

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(999x0:1001x2)/Keith-Urban-and-Nicole-Kidman-092925-fb84103d354b43ec9ba325e9671766a2.jpg?w=1200&resize=1200,0&ssl=1)