Wealthy business leaders are turning on US President Donald Trump over his plan to impose a colossal set of tariffs on America’s trading partners, as losses mount on stock markets around the world.

Billionaire investor Bill Ackman, who endorsed Trump’s 2024 presidential bid, warned Sunday that going ahead with the new tariffs was tantamount to launching an “economic nuclear war.”

On Wednesday, Trump said he would impose significantly higher “reciprocal” tariffs on dozens of countries that have the highest trade imbalances with the United States.

In a post on X, Ackman said “business investment will grind to a halt, (and) consumers will close their wallets” if the new levies do indeed come into force. “We will severely damage our reputation with the rest of the world that will take years and potentially decades to rehabilitate,” he added in the post, which was viewed 10.6 million times.

Unless Trump changes tack, “we are heading for a self-induced, economic nuclear winter, and we should start hunkering down,” the CEO of Pershing Square Capital Management warned.

“What CEO and what board of directors will be comfortable making large, long-term economic commitments in our country in the middle of an economic nuclear war?” he said, adding that “the president is losing the confidence of business leaders around the globe.”

Already Trump’s baseline 10% tariff on all goods imports into the US went into effect Saturday, and dozens of economies are bracing for even higher levies starting Wednesday. Those harder-hit countries include major US trading partners China and the European Union, which face new duties of 34% and 20% respectively.

Other billionaires and wealthy business leaders have also openly criticized Trump’s tariff agenda in recent days as fear over its economic fallout gripped markets.

Jamie Dimon, CEO of JPMorgan Chase, warned Monday that the tariffs threatened to raise prices, drive the global economy into a downturn and weaken America’s standing in the world.

“The recent tariffs will likely increase inflation and are causing many to consider a greater probability of a recession,” Dimon said in an annual letter to shareholders. “Whether or not the menu of tariffs causes a recession remains in question, but it will slow down growth.”

Billionaire Stanley Druckenmiller, founder of the Duquesne Family Office, an investment firm, said in a post on X Monday that he did “not support tariffs exceeding 10%.” Druckenmiller is worth an estimated $11 billion, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index.

Later in the day, billionaire Ken Fisher, the founder and executive chairman of Fisher Investments, said on X: “What Trump unveiled (last) Wednesday is stupid, wrong, arrogantly extreme, ignorant trade-wise and addressing a non-problem with misguided tools. Yet, as near as I can tell it will fade and fail and the fear is bigger than the problem, which from here is bullish.”

Fisher noted that he does not typically comment publicly on presidential actions, “but on tariffs Trump is beyond the pale by a long shot.”

Even Elon Musk — the world’s richest man and top Trump acolyte — said Sunday that he hoped for a “zero-tariff situation” between Europe and the US. In an interview with Italy’s Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini via video link, Musk said he wanted to see an effective “free-trade zone” created between Europe and North America.

Echoing Ackman, Simon MacAdam, deputy chief global economist at consultancy Capital Economics, said businesses were likely to hold off making investments due, in large part, to the “sheer uncertainty” of Trump’s tariff policy.

“If you’re a mid-sized or even a large-cap company, you’re going to be very hesitant about what to do,” he said.

“If those tariffs are going to be negotiated back down again in a few months’ time, then you’d be wasting your time investing potentially hundreds of millions of dollars in new plants… in the US,” he told CNN.

In his post, Ackman said the new tariffs were “massive” and “disproportionate,” saying: “This is not what we voted for.” He called for a 90-day “time out” in which Trump could negotiate with trading partners to “resolve unfair asymmetric tariffs deals.”

Trump has said his tariff agenda is designed to redress years of lopsided trade between America and its partners, caused, in his view, by other countries imposing steeper tariffs on US goods imported into their markets than the US does on theirs.

But investors are clearly not convinced by the wisdom of Trump’s plan. Stock markets in Asia and Europe plunged Monday and futures pointed to another bad day for US stocks, following Trump’s tariffs announcement last Wednesday.

Trump wants his tariffs to reset the world. He might get his wish

President Donald Trump has repeatedly touted what he calls the return of manufacturing to the United States, hailing companies that have vowed to pour large amounts of money into making everything from computer chips to cars in America.

But announcements are easy to make. In the long term, why would companies and other countries decide to invest in the US, which has upended the global economic order in just weeks? The United States moved from a stable economy, a trusted partner in trade agreements and global security, to a source of confusion and doubt in mere weeks after Trump assumed office on January 20.

Perhaps no one has put it more bluntly than Ursula von der Leyen, the president of the European Commission, on Wednesday, when she said to a news outlet in Germany: “The West as we knew it no longer exists.”

In other words: The United States isn’t the only trade game in town.

Sure, the US is the world’s biggest economy, with a gross domestic product of almost $30 trillion. But China, the world’s No. 2 economy, is at about $18 trillion, according to the World Bank. And the total value of the European Union’s economy is around 17 trillion euros, or about $19 trillion.

“We have 166 members in the organization. US trade is 13% of world trade. That means that there’s 87% of world trade happening between the other members of the WTO,” Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, director-general of the World Trade Organization, told CNN’s Richard Quest on Wednesday.

Trump has repeatedly claimed that other countries have been “ripping off” the United States for years, despite American growth rates that have been the envy of the developed world. So far, he has imposed 25% tariffs on aluminum and steel; 25% tariffs on goods from Mexico and Canada that aren’t compliant with a free-trade agreement; a massive 145% duty on Chinese imports; a 25% tariff on cars, with separate tariffs on auto parts coming at a later date; and a 10% baseline tariffs on all US imports.

But those numbers don’t quite capture the whiplash-inducing speed with which Trump has levied tariffs, then walked them back, only to announce more tariffs, with another policy change soon after. The constantly changing playing field has made it even more difficult for businesses and nations to contend with the new policies.

The tariffs in place now “will likely slow global economic growth significantly,” Moody’s Ratings said in a recent report. “And the inconsistent approach to policymaking has undermined confidence globally.”

The changes have been not only swift but also deep.

“These are very fundamental policy changes,” Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell said at an event hosted by the Economic Club of Chicago on Wednesday. “There isn’t a modern experience of how to think about this.”

His comments sent US stock markets slumping, with investors clearly uneasy about what it means when a usually staid central banker suggests the world economic order is being turned topsy-turvy. (Trump ripped Powell on social media the next day, ostensibly for not lowering interest rates quickly enough, writing: “Powell’s termination cannot come fast enough!”)

Already, as CNN’s Allison Morrow points out, companies and individuals are seeing real-world effects, from chipmaker Nvidia to aircraft maker (and top US exporter) Boeing, all the way to people shopping for cheap clothing or makeup hauls on Temu and Shein.

China, for its part, has been diversifying its trading relationships beyond the US since its trade war with the US during Trump’s first administration. China’s exports to the US dropped from 19.2% of its total overseas shipments in 2018, to 14.7% in 2024, said Sheng Laiyun, deputy director of China’s National Bureau of Statistics, at a news conference Wednesday. Reuters reported last week that Beijing is trying to strengthen trading with the EU, despite the occasional past spat over cheap goods and trade flows.

When asked by a reporter on Thursday if he was worried about China cozying up to US allies, Trump denied the possibility. “No, no,” he said. “Nobody can compete with us, nobody.”

But China isn’t alone in distancing itself from the US. Many Canadians have already canceled trips to the US to boycott Trump’s tariff policy. Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney last week posted on social media about speaking with von der Leyen.

“Throughout our history, Canada and Europe have worked together to build up our economies and bolster our shared security,” he wrote. “In this time of global uncertainty, we’re focused on making our relationship even stronger.”

Von der Leyen echoed those comments Wednesday, noting that more governments, including Canada, Mexico and India, have said they want to work more with the EU.

“Everyone is asking for more trade with Europe — and it’s not just about economic ties,” she said. “It is also about establishing common rules and it is about predictability. Europe is known for its predictability and reliability, which is once again starting to be seen as something very valuable.”

Christine Lagarde, head of the European Central Bank, pressed for European unity ahead of Trump’s April 2 announcement on so-called “reciprocal” tariffs.

“I consider it a moment when we can decide together to take our destiny into our own hands, and I think it is a march to independence,” she told France Inter radio.

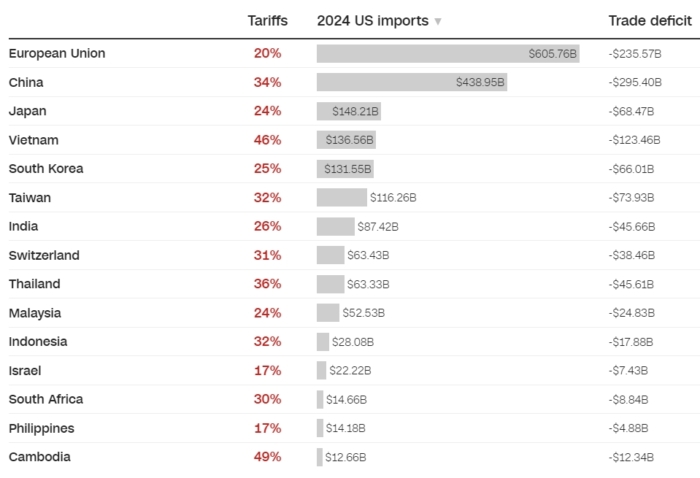

These are the hardest-hit US trading partners under Trump’s tariffs

President Donald Trump unveiled sweeping 10% tariffs on all imports to the United States Wednesday. About 60 countries or trading blocs will see even higher rates in an escalating move that is poised to initiate a global trade war.

How Trump’s ‘reciprocal’ tariffs will affect America’s trading partners

Trump has announced 10% tariffs on imports from any country into the United States, and even higher tariffs for the following 60 trading partners that have a high trade deficit with the US.

Countries or blocs subject to tariff rates higher than the 10% base rate

Many major US trading partners will be hit hard by Trump’s so-called reciprocal tariffs.

China is levied with a 34% rate, which is additional to the existing 20% duties on all Chinese imports to the United States, while the European Union gets 20%.

China and the EU accounted for around a quarter of US total imports in 2024 and are in the top three suppliers of US imports along with Mexico, according to US Census Bureau data.

Many Southeast Asian countries will also be heavily affected. Among them, Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia will see unprecedented rates of 46% to 49%. These are countries that Americans rely on for consumer goods, machinery and electrical goods and textiles.

Mexico and Canada are exempted from the list. But the existing 25% tariff on their exports to the US that don’t comply with the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement remains in place, except for Canadian energy and potash, which is tariffed at 10%.

The additional country-specific reciprocal tariffs also won’t add on to product-specific tariffs that have been announced on steel, aluminum and autos.

Rates applied are not reciprocal and don’t account for actual tariff rates

Trump pitched the tariff as “reciprocal,” where the rates would be based on the tariff rate that trading partners charge the United States when factoring in currency manipulation and other trade barriers. But that is not the case.

Instead the reciprocal rates follow a simple formula: the country’s trade deficit divided by its exports to the United States, then halved. The calculation was first suggested by journalist James Surowiecki in a post on X and backed up by Wall Street analysts.

For example, America’s trade deficit with China in 2024 was $295.4 billion, and the United States imported $439.9 billion worth of Chinese goods. That means China’s trade surplus with the United States was 67% of the value of its exports — a value the Trump administration labeled as “tariff charged to USA.”

Half of that 67% rate is the 34% reciprocal tariff rate set for China.

This means that tariffs from other countries were not really factored into the calculation. Instead, the measures target countries with large trade surpluses relative to their exports to the United States, noted Mike O’Rourke, chief marketing strategist at Jones Trading, in a note to investors Wednesday.

This is how Lesotho, a country with which the United States has a $234 million trade deficit — nowhere near its $295 billion deficit with China — ended up with the steepest 50% reciprocal rate.

The baseline 10% tariff will go into effect on Saturday, and any higher tariffs will go into effect on April 9.

Not feeling the trade war pain yet? Get ready

Trump says he’s punishing foreign countries. He’s mostly punishing Americans

And perhaps most quixotically, Trump seems to believe we can undo decades of globalization and bring back the manufacturing jobs we already shipped overseas. (Even if we could “reshore” those industries, it would take many, many years.)

“There is no strategy,” said Mary E. Lovely, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute, during a Brookings Institution event Thursday. “Are we supposed to knit our own knickers?”

Lovely added: “When people say they want manufacturing in the US, they’re saying high-tech, sustainable jobs” — not the lower-skilled and labor-intensive jobs that have migrated to developing economies.

“I think a great exercise is everybody go home, and when you’re dressing tonight for bed, look at where your clothes are made,” Lovely said. “All of these countries have large deficits, and that gives them the high ‘reciprocal’ tariffs.”

Bad math

Lovely and others have made the point that if you wanted to balance out some trade deficits, there are strategic ways to do it. Maybe you’d assemble a team of leading economists and policy experts and take a scalpel to each trade agreement and figure out where you have leverage.

But Trump’s government did not do painstaking dollar-for-dollar studies to try to nail down an accurate rate for each trading partner.

Instead, it took a country’s trade deficit, divided it by its exports to the United States, then divided that number by two. That’s it.

A lot of analysts were shocked by that sledgehammer approach.

“If a ninth grader in high school presented this tariff chart to a teacher in a basic economics class, the teacher would laugh and say ‘sit down and work on the assignment,’” Wedbush Securities analyst Dan Ives wrote in a note on Thursday.

Or, as Lovely put it: “It’s like going to your doctor, finding out you have cancer, and the basis for your medication is your weight divided by your age.”

Here’s my favorite part, though: When economist and author James Surowiecki figured out the convoluted formula, the White House tried to say he was wrong and released a scary-looking equation with Greek letters to try to illustrate the very sophisticated math they used to calculate this monumental change to global economic policy.

Turns out, that equation worked out to exactly what Surowiecki said it was, just dressed up with symbols that make it look more complicated — and to intimidate people who question what they’re doing, as economist Brendan Duke told me.

That is not economic policy — it is Russian roulette in an economic policy costume.

“Oh sh—”

Since the president’s Orwellian “Liberation Day” speech, the global response hasn’t exactly been celebratory.

Stocks began tumbling almost immediately, shedding trillions of dollars in market value overnight. All three major US indexes posted their biggest single-day drop since 2020.

Global leaders expressed shock; and some, including allies like France and Canada, promised to retaliate. Oil fell more than 6%. Stellantis, the carmaker behind Jeep and Chrysler, is already laying off 900 American workers and pausing production at some of its Canadian and Mexican plants, citing the impact of tariffs.

When the CEO of RH (formerly Restoration Hardware) saw his company’s stock fall 40% during an earnings call Wednesday evening, shortly after Trump’s speech, he uttered two words that just about summed up the thoughts of every other executive that day: “Oh, sh—.”

Shares of multinational companies like Nike and Apple were hit hard, as were retailers like Five Below and Dollar Tree, which rely heavily on cheap imports from Asia.

“This is the policymaking equivalent of a suicide bomber,” Michael Block, market strategist at Third Seven Capital, told my colleague Matt Egan. “They’re ignoring every rule of classic micro and macroeconomics.”

So that’s the word on the Street, the institution that Trump has previously viewed as a real-time report card on his presidency.

On Thursday, though, Trump shrugged off the market reaction, telling reporters: “I think it’s going very well.”

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(999x0:1001x2)/catherine-ohara-013026-7-4b5b413a646d4f15a1fd15ac8b933811.jpg?w=1200&resize=1200,0&ssl=1)