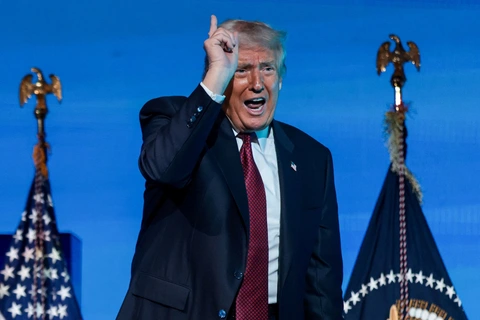

“We don’t have inflation,” President Donald Trump said in an interview with CBS last weekend, asserting that “food prices are going down.”

It wasn’t the first time he made such a claim. In recent months, Trump has repeatedly declared that the U.S. is not facing inflation, arguing that energy and consumer prices are falling — part of his ongoing push for the Federal Reserve to cut interest rates.

Reports show that inflation is indeed far below its peak under former President Joe Biden’s administration. But it hasn’t disappeared. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) in September rose 3% year over year — lower than expected, but still the highest since January and above the Fed’s 2% target.

Inflation eased during the first four months of the year but picked up again later, partly due to higher import tariffs.

According to a new CNN poll, 72% of respondents say the economy feels unstable, while 47% list the economy and cost of living as their top concerns. Another survey by ABC News and The Washington Post earlier this month found that two-thirds of Americans believe the economy is “seriously off track,” and about 60% blame Trump for current inflation levels. The same percentage disapprove of his handling of tariffs, economic policy, and federal management.

Analysts warn that the president may be repeating his predecessor’s mistake — denying the economic pain that Americans are feeling.

In June 2022, with gas prices hitting record highs and inflation at a 40-year peak, then-President Biden downplayed the crisis by emphasizing economic growth instead. “Look, we’re the fastest-growing economy in the world,” he told ABC, while acknowledging inflation was a challenge but insisting price increases were “mostly about food and gas.”

That tone-deaf response, many argue, contributed to the Democrats’ losses in last year’s presidential election. By 2024, affordability had become Americans’ biggest worry — and even though inflation slowed, prices stayed high.

“Wages are up, inflation has cooled from 9% to 3%. It’s the lowest in the world and still falling,” Biden declared in his 2024 State of the Union Address. But voters were unconvinced. His speech ignored the cumulative toll that rising prices had already taken on American households.

Trump’s approach differs in tone but may lead to the same outcome. While Biden admitted prices were still rising, Trump is flat-out denying that inflation exists at all.

Analysts note that Americans tend to react negatively when politicians dismiss their lived experiences — especially when they’re reminded daily at grocery stores, gas stations, and rent offices of how much more things cost.

Trump once used inflation as a political weapon against Biden, accusing his predecessor of being out of touch with the public’s economic pain. During campaign stops, Trump would sometimes pose with grocery items, pointing out how expensive they’d become.

But after taking office, inflation has become his own political problem — one he can no longer blame on the previous administration. A new CNN poll found that roughly 60% of Americans now say Trump’s policies have made the economy worse.

Beyond frustration with high prices, consumers are changing their behavior. In recent earnings reports, companies like Chipotle, Coca-Cola, and Crocs said middle- and lower-income customers had begun cutting back on spending.

Even though overall economic data remains strong, weakening job growth and the winding down of federal support programs have stoked public anxiety. Defaults and late payments are also ticking up again.

The underlying issue is cumulative inflation. Years of price increases have left goods far more expensive, even if inflation’s pace has slowed dramatically since Biden’s time in office.

According to Moody’s Analytics, the average American household now spends $208 more per month than it did in September 2024 for the same basket of goods and services. Compared with early 2021, that figure jumps to $1,043 more per month.

Last week, after the Fed announced a rate cut, Chair Jerome Powell remarked that “consumers don’t care about political narratives.”

“The prices they pay are higher,” Powell said. “You can say inflation isn’t rising as fast, but people clearly see their costs are much higher than two or three years ago.” He added that inflation “remains very frustrating for the public.”

Powell noted that time — and wage growth — would help ease the pressure. “They’ll feel better eventually, but it’s going to take time,” he said.

In a book published earlier this year, Democratic strategist David Plouffe reflected on what he called his party’s major mistake: denying the reality voters were living.

“As the party in power,” he wrote, “we should never tell people that what they’re seeing with their own eyes isn’t real.”

Trump’s dollar delusion: how trade war risks ending the US’s ‘exorbitant privilege’

Trump’s team flirts with weakening the dollar, threatening US influence, low borrowing costs and global stability

Magical thinking is indispensable to understanding Team Trump’s economic policymaking. The White House often seems to believe two opposing policies can work together while one policy can do two or three contradictory things.

A heavy dose of hocus pocus will be needed to make the administration’s dollar policy work in the interest of the United States, for it appears that they want to end the US dollar’s supremacy in global finance.

At least some part of it does. True, Donald Trump has warned countries not to replace the dollar, or else. And, reportedly, some members of the administration want to encourage more countries to adopt the dollar outright. But what is also true is that Stephen Miran, the president’s chief economic adviser, on leave to act as board member of the Federal Reserve, thinks the dollar’s position as the main reserve currency of the world is an undue burden for the US and a principal driver of the large trade deficit that Trump finds so odious.

“America runs large current account deficits not because it imports too much,” Miran wrote last year. Rather, it imports too much because it must export Treasury bonds to provide other countries with assets in which to park their reserves. This leads to “persistent dollar overvaluation that prevents the balancing of international trade.”

The quote brings to mind Jenny Holzer’s 1980s Times Square billboard, with its dry appeal to a higher power: “protect me from what I want.”

It is not impossible that Trump & Co. could effectively debase the dollar. They could do it through policy choice or sheer incompetence. Arguably, they have already started. They will not like the outcome.

For sure, foreign countries will suffer if US Treasury bonds quit their job as safe liquid assets in which to park reserves. There are no good alternatives out there. The old hope that the euro would rival the dollar has been stymied by Europe’s fragmented capital markets. A quarter century from the euro’s launch there is no euro T-bond. The renminbi, meanwhile, can’t play a leading role in global finance while China retains capital controls that keep money from freely flowing in and out.

The dollar is valuable not only as a financial haven. A recent research paper points out that roughly two thirds of countries in the world stabilize their currency against the dollar to provide insurance against global economic shocks. Because the US market is so large, the value of the dollar affects the price of traded goods: shocks that appreciate the dollar also raise their price. Holding dollars or, indeed, aligning one’s currency with the dollar – can help hedge against these economic fluctuations.

The cost of undermining the dollar to the US would also be enormous. For starters, it stands to lose world influence, alongside its main tool for economic coercion, which allows it to limit enemies’ access to the financial system. Moreover, the US would relinquish what former French president Valery Giscard d’Estaing called the US’s “exorbitant privilege”.

Miran is not wrong that the dollar’s reserve status draws a lot of money into Treasury bonds. But that is a gift. It allows the government to fund its massive debt – 120% of GDP – at a low interest rate. The privilege also implies that the US earns more on its holdings of foreign assets than foreigners earn on their US holdings. Indeed, curbing the US current account deficit would be much more difficult if the US lost its reserve status because its interest rate edge would shrink or disappear altogether.

Which brings us to the question, will Trump knock the dollar off its perch? Its supremacy has been eroding. These days it accounts for 58% of global foreign exchange reserves, down from 74% at the turn of the century. The interest rate advantage Treasury bonds have over the debt of corporations or other countries has shrunk over time.

And Trump’s trade war will reduce the dollar’s insurance powers. By curbing US imports, Trump’s tariff wall will dampen the relationship between the dollar and the price of traded goods–reducing its value as a hedge against economic shocks. “We’re basically reducing the impact that we have on the world market, and by reducing the impact that we have on the world market, we also reduce the dollar safety property,” notes Tarek Hassan of Boston University.

And that gives countries and investors less of a reason to peg their currency to the greenback or hold dollar assets. Hassan estimates that the tariffs imposed so far have raised US interest rates by half a percentage point, a not-irrelevant amount given that rates are in the 3-4% range. Developing countries have been swapping out of dollar debt in recent months, turning to currencies with lower interest rates like the Swiss franc and the renminbi.

The notion that the president’s trade war might undermine the dollar’s pre-eminence struck hard on “Liberation Day” in April when Trump first announced his round-robin “reciprocal” tariffs. US stocks, bonds and the dollar plunged in unison, like risky emerging market assets, breaking the ironclad rule of modern finance that shocks to the system, whether coming from the US or some faraway developing country, benefit Treasury bonds and the dollar as the world’s safe haven, where governments, investors and regular people park money in times of unrest.

Markets have calmed down since then. Investors appear to have forgiven Trump for the incoherent policymaking. Maybe it’s because Trump ultimately walked back many of the tariffs. But blood is in the water. The odds that the Treasury bond will lose its primacy as the world’s safest asset are looking shorter.

Who knows what that would entail? Other currencies might fill some of the slack. Europe’s joint effort to rearm, for instance, could open an opportunity for euro-wide bonds to rival US Treasury bonds in other countries’ foreign exchange reserves. But insurance against economic and financial shocks will likely become more expensive. Global welfare will surely suffer.

Trump & Co might at first applaud a cheaper dollar, which would likely translate into a smaller US trade deficit. The cheers, however, are unlikely to last. This would come, for the US, at an exorbitant cost.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(752x402:754x404):format(webp)/aaron-foster-dog-011426-3-6fc3c908a2ef4bd4aa9db8d9c3dc4c25.jpg?w=1200&resize=1200,0&ssl=1)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(999x0:1001x2)/catherine-ohara-013026-7-4b5b413a646d4f15a1fd15ac8b933811.jpg?w=1200&resize=1200,0&ssl=1)