KANANASKIS, Alberta (AP) — A Canadian Indigenous leader who greeted world heads of state arriving for the Group of Seven summit says he was “filled with rage” and considered leaving before Donald Trump arrived — saying the U.S. president has “caused much pain and suffering in the world.”

Instead, Steven Crowchild prayed, consulted with his peoples’ leaders and ultimately opted to stay on the tarmac for a long conversation with Trump that he hopes will call more attention to promoting peace, protecting clean water and other issues key to Canada’s First Nation peoples.

“It was really intense, to say the least,” Crowchild told The Associated Press on Monday, recalling his lengthy encounter with Trump on Sunday night in Calgary for the G7 in nearby Kananaskis. “When I woke up on Father’s Day, I didn’t anticipate I would be seeing world leaders, and one certain individual that has caused much pain and suffering in the world.”

In Canada, First Nations refers to one of three major legally recognized groups of aboriginal people. Crowchild, of the Tsuut’ina First Nation, is a Tsuut’ina Isgiya and a current elected member of the Tsuut’ina Nation Xakujaa-yina and Chief and Council.

Crowchild said he spoke in his people’s traditional language, wore feathered headgear that made him feel strong and showed Trump treaty medals that he told the president were older than Canada itself. Trump wore a white “Make America Great Again” cap and appeared to be listening at length — though both sides declined to comment on exactly what was said.

“When it came to that one individual, I almost didn’t stay. I was filled with rage,” Crowchild said. “I was going to go home because I didn’t want to bring any negativity to my people. However, I did consult with close people and advisers and, based on feedback, I stayed, considering that visibility is key and diplomacy is important.”

Aware that “no Indigenous representation was there at the time,” Crowchild said he “prayed to my creator” and “really thought of those suffering around the world” in choosing to speak to Trump.

“Instead of war, I choose peace,” he said.

Crowchild said that, in addition to Trump, he greeted other arriving world leaders and “tried to remind each one of them to try to be a good leader and protect our water for future generations.”

“I spoke for my elders,” Crowchild said, noting that he spoke of promoting peace and “protecting water for future generations” and tried to “say as much as I could, as wisely as I could, while representing with honor and dignity. Whether he listened or not, time will tell.”

He said that, ultimately, the U.S. president is “just another person.”

“Some would say he’s a horrible person, and we all know many reasons,” Crowchild said. “I stood taller than him as proud Tsuut’ina Isgiya.”

___

Weissert reported from Banff, Canada.

Los Angeles Residents Outraged by Trump’s Pressure and Military Deployment

Trump is facing heat from all sides, but his fateful Iran decision is one only he can make

President Donald Trump is under opposing pressure from inside Israel and his own MAGA base as he ponders the most fateful national security decision of either of his presidencies — whether to attempt a killer blow against Iran’s nuclear program.

Israel is sending clear signals, including through former senior officials, that it hopes the US will ultimately join the conflict and use its unique military edge to destroy the Iranian nuclear complex at Fordow, which is buried deep underground.

“We believe that the United States of America and the president of the United States have an obligation to make sure that the region is going to a positive way and that the world is free from Iran that possesses (a) nuclear weapon,” former Israeli Defense Minister Yoav Gallant told CNN’s Bianna Golodryga in an interview.

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, meanwhile, used an ABC News interview Monday to pour cold water on a diplomatic channel with Iran that Trump seems desperate to revive, saying it had been used to “string the US along.”

A sense that an entwined political and national security crisis is building was exacerbated by Trump’s decision to suddenly leave the G7 summit in western Canada on Monday night.

“I have to be back early for obvious reasons,” Trump said. “They understand. This is big stuff.”

He flies home to Washington as it reverberates with blunt warnings from some of the most influential opinion shapers in MAGA media. Personalities like Steve Bannon and Tucker Carlson say that a decision to strike Iran would represent a repudiation of his 10-year-old political movement and “America First” principles. ”I don’t want the US enmeshed in another Middle East war that doesn’t serve our interests,” Carlson said on Bannon’s “War Room” show on Monday.

Synergy between right and left populist movements in America is also on display. Vermont independent Sen. Bernie Sanders, who ran as a Democrat primary candidate in the 2016 and 2020 elections, said the US “must not get dragged into another of Netanyahu’s wars.”

Loud voices opposed to deeper US involvement underscore the painful legacy of the Iraq and Afghan wars, which created political forces that nurtured Trump’s populist uprising. But the neoconservative interventionist wing of the GOP has not disappeared. Hawks like Sen. Lindsey Graham are trying to convince Trump that Israel’s blitz against Iranian air defenses and a confluence of forces that have weakened the regime offer the US a chance to definitively end the nuclear aspirations of its 45-year foe and to transform the Middle East.

European leaders who met Trump in Canada brought to bear their own pressure, seeking to see whether the US will rein in Netanyahu amid concern over Trump’s suggestion that Russian President Vladimir Putin might join a peace effort.

Even Iran joined the cacophony, accusing Israel of sabotaging US nuclear talks with the Islamic Republic, a centerpiece of the president’s so far frustrated strategy of branding himself as a global peacemaker.

A decision that will define Trump’s presidency … and much more

Multiple voices bearing down on Trump reflect the gravity of a decision that will carry consequences that go beyond the always-heavy burden of whether to send American personnel to war.

Whatever he decides, Trump will set off consequences that will be pivotal for Israel’s security, the wider Middle East, and US power and influence. He can’t know whether a US attack on subterranean chambers in Fordow could succeed or whether it will suck the US deeper into a prolonged conflict.

Historically, Trump has balked at perceptions that his options are being narrowed — or that others are trying to make up his mind for him. So pressure from any direction risks being counterproductive.

Ironically, Trump set up this dilemma himself. His decision to walk away from a previous US nuclear deal with Iran in his first term delighted Israel — but laid the groundwork for a future crisis.

The raging debate in the MAGA movement that is splitting conservative media is a sign that Trump’s own support base is on the line, and that a legacy he promised would not be marked by foreign interventionism is also at stake.

Trump often creates shock and disorientates opponents by igniting confrontations that he later defuses or postpones. This is his preferred approach to trade wars. But there would be no going back from a US military strike with bunker-busting bombs at Fordow. Whatever the aftermath, the president would own it.

This may explain why he avoided committing himself to any course of action on Monday. He said Iran has “to make a deal” and should talk immediately “before it is too late.” But pressed by reporters on what would cause a direct US intervention in the conflict, he replied, “I don’t want to talk about that.”

On Monday evening, the president wrote on Truth Social that “IRAN CAN NOT HAVE A NUCLEAR WEAPON” and said everyone should “immediately evacuate Tehran,” although he did not explain why he would issue such a warning.

Perhaps Trump is just playing for time or trying to scare Tehran back to the table. But maybe he really doesn’t know what he’s going to do.

A task only the US can accomplish

Iran has so far not directly targeted US bases or personnel, nor has it widened the conflict — for instance, by going after shipping in the Strait of Hormuz, which could trigger global economic shockwaves. That may be a sign that it wants to avoid pulling Trump in. But it is generally agreed that while Israel can delay Iran’s nuclear program, only the US can destroy it.

In an extraordinary interview with CNN’s Golodryga, Gallant warned that Trump had the future of the world in his hands.

“This could be a disaster for the world,” he said, referring to the possibility of an Iranian bomb. “And I believe that the determination of the American president that has been shown recently will pave the way to America to enter into this very important operation,” Gallant said. “The president of the United States (has) the option to change the Middle East and influence the world.”

Another former Israeli defense minister, Benny Gantz, also noted unique US military assets. “I do remember that the United States is much stronger than us. It has capabilities that we don’t possess. But I’m not in a position to recommend to the president of the United States what to do,” Gantz told CNN’s Anderson Cooper. “I am sure that the United States, if it decides to act, will do it for its own interests and not our interests only.”

Israel’s President Isaac Herzog implied that Trump had been taken for a ride in his pursuit of a diplomatic solution. “You can speak (of a) peaceful diplomatic (solution), and on the other hand, underneath you move forward to the bomb. And that was exactly the situation,” Herzog told Wolf Blitzer on “The Situation Room.”

And Netanyahu aimed a message at Trump’s MAGA critics. “Today, it’s Tel Aviv. Tomorrow, it’s New York. Look, I understand ‘America First.’ I don’t understand ‘America Dead’. That’s what these people want,” Netanyahu told ABC.

‘We have to think this through’

A sincere debate over Iran is underway inside Trump’s grassroots movement, and it is causing splits across the right-wing media empires that normally support the president unequivocally.

Bannon argued that a major new US escapade in the Middle East would deviate from the core principles of Trumpism, which involved avoiding “forever wars,” expelling undocumented migrants, securing the border and confronting China to bring back US manufacturing jobs. He said on “War Room” that Israel had to make sovereign decisions for itself, as any nation should. “But when you start making decision that are predicated on the assumption that America is going to come in, not just for defense but for offense … No, we have to make decisions that put America first.”

Bannon went on: “This has to be thought through. This Pearl Harbor-type attack on the mullahs is fine for Israel. But is it right for the United States?” He concluded that the real war that the US faces is against undocumented migrants on its own soil.

A fundamental question underpins this internal MAGA debate: If “America First” is not about avoiding the kind of Middle East quagmires that that ruined President George W. Bush’s Republican presidency, does it really mean anything?

Trump’s political success was forged in the US heartland, in the kind of towns that sent their young to fight and die in the post-9/11 wars. Those conflicts started with shock-and-awe initial success like the one Israel is celebrating with its elimination of top Iranian military leaders and nuclear scientists. But they degenerated into bloody slogs that still haunt American politics. No one is openly talking of a betrayal yet. But just a month ago, in Saudi Arabia, Trump restated his opposition to interventionism and nation-building in the Middle East.

On the left, there was already antipathy toward Netanyahu because of the terrible toll on Palestinian civilians of his war on Hamas. But Sanders also seemed to be vying for Trump’s attention, warning in a statement, “The attack was specifically designed to sabotage American diplomatic efforts: Israel assassinated the man overseeing Iran’s nuclear negotiating team, despite the fact that further talks with the United States were scheduled for Sunday.”

An allergy to such foreign entanglements is not just endemic to Trump’s political project: His two predecessors, Barack Obama and Joe Biden, felt much the same way.

But now it’s fallen to Trump to make a decision that every modern president dreaded.

Judge extends order suspending Trump’s block on Harvard’s incoming foreign students

President Donald Trump’s order to block incoming foreign students from attending Harvard University will remain on hold temporarily following a hearing Monday, when a lawyer for the Ivy League school said Trump was using its students as “pawns.”

US District Judge Allison Burroughs in Boston extended a temporary restraining order on Trump’s proclamation until June 23 while she weighs Harvard’s request for a preliminary injunction. Burroughs made the decision at a hearing over Harvard’s request, which Trump’s Republican administration opposed.

Burroughs granted the initial restraining order June 5, and it had been set to expire Thursday.

Trump moved to block foreign students from entering the US to attend Harvard earlier this month, citing concerns over national security. It followed a previous attempt by the Department of Homeland Security to revoke Harvard’s ability to host foreign students on its campus in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Burroughs has temporarily blocked that action, too, and is weighing whether it should remain on hold until the case is decided.

Ian Gershengorn, a lawyer for Harvard, told Burroughs on Monday that Trump was “using Harvard’s international students as pawns” while arguing the administration has exceeded its authority in an attempt to retaliate against the school for not agreeing to the president’s demands.

“I think there is no finding that Harvard is dangerous,” he said.

Trump has been warring with Harvard for months after it rejected a series of government demands meant to address conservative complaints that the school has become too liberal and has tolerated anti-Jewish harassment. Trump officials have cut more than $2.6 billion in research grants, ended federal contracts and threatened to revoke its tax-exempt status.

Foreign students were brought into the battle in April, when Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem demanded that Harvard turn over a trove of records related to any dangerous or illegal activity by foreign students. Harvard says it complied, but Noem said the response fell short, and on May 22 she revoked Harvard’s certification in the Student and Exchange Visitor Program.

The sanction immediately put Harvard at a disadvantage as it competed for the world’s top students and harmed Harvard’s reputation as a global research hub, the school said in its lawsuit. “Without its international students, Harvard is not Harvard,” the suit said.

The action would have upended some graduate schools that recruit heavily from abroad. Some schools overseas quickly offered invitations to Harvard’s students, including two universities in Hong Kong.

While Harvard’s legal team on Monday said the federal government was unfairly and illegally singling the university out in Trump’s proclamation, Department of Justice attorney Tiberius Davis countered that the administration has scrutinized dozens of universities over the past two months.

“The power is within Harvard to fix this,” Davis said, adding that currently the federal government believes “other universities might be better” to host foreign students.

Davis was the sole attorney to attend and defend the Trump administration during Monday’s hearing compared with the six Harvard attorneys, a contrast that Burroughs commented on repeatedly.

“Not only do you have this case but you have it alone,” she said.

Harvard President Alan Garber previously said the university has made changes to combat antisemitism. But Harvard, he said, will not stray from its “core, legally-protected principles,” even after receiving federal ultimatums.

Why it will be hard for Trump to stay out of the conflict with Iran

President Donald Trump is desperate not to fight a war with Iran.

But can he really avoid it?

Compelling national security arguments and domestic political considerations mean it makes sense to stop short of direct US offensive operations in the long-dreaded conflict that Israel describes as a matter of preserving its own existence.

But powerful forces could suck America deeper into the conflict than its current role in helping to shield Israel from Iran’s deadly rain of missiles and drones.

CNN reported that over the weekend, Trump rejected an Israeli plan to kill Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, according to two sources.

But some of this is out of Trump’s hands.

Should Iran’s battered regime decide it has nothing to lose and attack US bases and personnel in the region, or US targets across the globe, Washington will be forced to respond hard to preserve credibility and deterrence. Another possibility is that Tehran could create duress on Trump to rein in Israel by attacking international shipping in the Gulf or Red Sea and bring on a global energy crisis.

Pressure is also mounting on Trump from inside his own party for action that only the United States could carry out — a mission to destroy Iran’s subterranean site at Fordow, which is believed to be beyond Israel’s airborne capabilities. The logic of such a strike would be that Iran is now uniquely vulnerable, and a better chance may never come for the US to destroy the possibility of an Iranian nuclear weapon.

Why Trump might see a reason to join the conflict

CNN’s White House team has reported that the president is deeply skeptical about throwing the United States into the fray. Such a move would be fraught with danger. It could lead to the expansion of the conflict beyond its current belligerents and lead to a grueling open-ended war with no clear endgame.

If there is one lesson from the early 21st century, it’s that war objectives and analyses of the Middle East drawn up in Washington almost always turn out disastrously wrong. The idea that Iran’s brutal clerical regime could fall might be attractive. But the toppling of Saddam Hussein and the civil war in Syria show that Middle East nations can simply splinter when power vacuums open.

A US intervention would also widen deep strains in Trump’s political base and dismantle a core principle of his “America first” movement: that the United States should stay out of foreign quagmires after more than a decade of pain in Iraq and Afghanistan. It is only a few weeks, after all, since the president set out a new vision for the Middle East and American involvement.

“The so-called nation-builders wrecked far more nations than they built — and the interventionists were intervening in complex societies that they did not even understand themselves,” Trump said in a major speech in Saudi Arabia in May. “A new generation of leaders is transcending the ancient conflicts and tired divisions of the past and forging a future where the Middle East is defined by commerce, not chaos; where it exports technology, not terrorism; and where people of different nations, religions and creeds are building cities together — not bombing each other out of existence.”

A new American war is utterly incompatible with such a vision. Still, hawks in Washington might argue that Trump has a unique opportunity to remove the major impediment to his vision by eradicating Iran’s path to a nuclear weapon or even contributing to the toppling of its theocratic leadership.

Presidents have often written in their memoirs about momentous and agonizing choices to deploy troops in foreign wars. Sometimes, however, a decision not to rush in even when it appears tempting requires as much courage.

Dilemmas like the one now facing Trump typically come with negative outcomes either way.

Republicans argue the US may have no choice but to get involved

Political heat is already mounting on the president to come off the sidelines even as the United States made clear that Israel’s decision to launch major attacks against Iran is its alone and that Washington’s forces have no offensive involvement.

One of the complicating factors for Trump is that while Israel’s attacks seem to have been successful in taking out top military leaders and nuclear scientists, it remains unclear whether Israel has the capacity to eradicate Iran’s nuclear program itself.

Former Vice President Mike Pence said on “State of the Union” Sunday that if Israel’s attack doesn’t somehow convince Iran to make major concessions in Trump’s diplomatic attempt to end its nuclear program, then the United States should be prepared to join the conflict.

“Now, if the Iranians want to stand down, I think the president’s made it clear he’s willing to enter into negotiations. But there can be no nuclear program of any kind, no enrichment program of any kind,” Pence told CNN’s Dana Bash. “And at the end of the day, if Israel needs our help to ensure that the Iranian nuclear program is destroyed once and for all, the United States of America needs to be prepared to do it, because this is about protecting our most cherished ally.”

Republican Sen. Lindsey Graham argued the worst possible outcome of a conflict between Israel and Iran would be for Tehran’s nuclear capabilities — which it has long denied are designed to build a bomb — to remain.

“If diplomacy is not successful, and we are left with the option of force, I would urge President Trump to go all in to make sure that, when this operation is over, there’s nothing left standing in Iran regarding their nuclear program,” Graham, a key Trump ally, said on CBS’ “Face the Nation.” “If that means providing bombs, provide bombs. If that means flying with Israel, fly with Israel.”

Trump risks a domestic backlash

These calculations are difficult enough. But Trump also faces a complex domestic political scenario that is the result of his own transformation of the GOP into a more isolationist party. This means he faces a different political scenario than the one before President George W. Bush when he went into Afghanistan and Iraq.

Some of the loudest voices on the right, including Tucker Carlson and Charlie Kirk, have already warned Trump against fracturing trust with the MAGA base by diving into a new Middle East war. The president has always been extremely careful with his own complex coalition. He’s loath to take steps that annoy his voters. One example was his turnaround last week in halting deportation sweeps against agricultural workers — partly to avoid angering farmers and employers in the rural heartlands where he draws much of his support.

Trump’s preoccupation with the political costs was evident in a conversation with journalist Michael Scherer of The Atlantic on Sunday.

“Well, considering that I’m the one that developed ‘America first,’ and considering that the term wasn’t used until I came along, I think I’m the one that decides that,” Trump told Scherer. “For those people who say they want peace — you can’t have peace if Iran has a nuclear weapon. So for all of those wonderful people who don’t want to do anything about Iran having a nuclear weapon — that’s not peace.”

The president appeared to be rehearsing an argument for his base that he’d have to use if he joined Israeli action. It’s fascinating to watch him wrestling with a conundrum between national security arguments that would face any conventional American president and the sectors of the political movement that lifted him to power. He doesn’t seem absolutely convinced yet by his own argument, perhaps because, as Kirk pointed out, younger male voters who flocked to his reelection campaign last year do not want to join a “quagmire” in the Middle East.

Trump’s foreign policy is unraveling

This is hardly where Trump hoped to be early in his presidency — one reason he appeared so bullish even as recently as this month about his effort to force Iran to agree a deal to peacefully end its nuclear program.

Trump started his second term vowing to be a peacemaker.

But five months in, two major wars raging when he took office are worse and the dangerous new conflict with Iran promises the greatest test of “America first” restraint.

Trump’s authority has been flouted by three key leaders: Russian President Vladimir Putin, Chinese President Xi Jinping and Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu. And his “art of the deal” approach to foreign policy is a failure.

Putin has ignored Trump’s efforts to end the Ukraine war. Xi has twice forced the US leader to fold in their trade war. And Netanyahu’s decision to launch the conflict with Iran that American presidents have long sought to avoid appears to have scuttled Trump’s Iran diplomacy — and is based on a bet that no American president could afford not to defend Israel even if he differed with its decisions.

At home, presidents must create public trust for their decisions to go to war. Here, Trump may struggle since he’s alienated millions of people with his searing approach to affairs at home. This includes his decision to deploy the military in California amid anti-ICE protests last week and warnings he plans to use troops everywhere.

Trump’s second term has already belied the notion that the weight of his personality, supposed respect for him among foreign adversaries, and what aides see as an almost magical dealmaking ability would change the world. The promised rush of trade deals shaken loose by his tariffs, for example, has not materialized.

Trump’s first peacemaking foray — in Gaza — failed. Hundreds of thousands of Palestinians are now facing starvation as Israel’s pounding of the Strip, triggered by Hamas’ attacks in October 2023, continues.

The president’s effort to end the Ukraine war never went anywhere. The conflict widened. It spread into Russia with Ukrainian raids on Russian bases that prompted Putin to launch vicious attacks on civilians in Kyiv and elsewhere. The White House made it known that Trump was getting frustrated with the Russian leader and set a two-week deadline to consider tougher sanctions on Moscow. But nothing revealed the risible nature of that spin and Trump’s biased attitude to the war more than his excitement on Saturday that Putin had called to wish him a happy birthday.

Events have overtaken Trump’s “American first” reticence to get involved abroad and exposed the shallowness of his statesmanship. Worsening crises may offer a preview of a world that becomes more volatile in the absence of steady and constant American leadership.

Trump’s increasingly brittle domestic political grounding and his already questionable authority internationally will only complicate his dilemmas. In many ways the Iran conflict is the kind of international crisis with no easy answers that he avoided in his first term.

Now it could define his second.

Americans’ – and Republicans’ – increasingly complicated relationship with Israel

The president who promised to easily and quickly bring about peace has now found himself accounting for yet another major escalation. President Donald Trump had publicly discouraged Israel from striking Iran in recent days, as he pushed to instead secure a deal to curtail Iran’s nuclear program.

But it didn’t pan out. Israel launched a massive attack overnight that targeted Iran’s nuclear facilities and killed high-ranking officials – strikes that Trump told CNN by phone early Friday were “very successful.”

It all reinforces how the world we live in is much more complex than the one Trump pitched on the campaign trail.

And from a domestic perspective, the situation with Israel is arguably more complex than it has been in many decades.

Multiple indicators suggest Americans’ support for Israel has reached historic lows as its war in Gaza has dragged on. And while Republicans are much more likely to back Israel than Democrats, even that is getting more complicated – particularly as influential voices on the right voice skepticism of a hardline approach to Iran.

Much remains to shake out amid the historic escalation in the Middle East. Things will shift. There is a real question about whether Iran is even capable now of the kind of significant retaliation that could lead to a wider war.

But the US decisions that lie ahead aren’t as easy as they once might have seemed, politically speaking.

A Quinnipiac University poll released this week – ahead of Israel’s strikes – epitomized the shifting landscape.

Polls for decades have asked Americans to choose whether they sympathize more with Israelis or Palestinians, and Israel is almost always the runaway favorite. But this one showed Americans sided with the Israelis by a historically narrow margin: 37% to 32%.

After Hamas’ October 2023 terror attack on Israel, that margin had been 61-13% in the Israelis’ favor. So a 48-point edge has shrunk to five.

That’s not only the lowest advantage for Israel since Quinnipiac began polling this question in 2001, but it appears to be about the lowest since at least 1980 across multiple polls, according to data compiled by the Roper Center for Public Opinion Research.

Those findings, while telling, don’t strictly apply to a conflict between Israel and Iran. But it’s also clear that overall support for Israel has waned over the past year and a half.

To wit:

- A March poll from the Pew Research Center showed 53% of Americans – a majority – had an unfavorable opinion of Israel. That was up from 42% in 2022, before the current war in Gaza. The same poll showed Americans said by more than a 20-point margin that they lacked confidence in Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

- A March poll from Marquette University Law School showed Americans evenly split on Israel: 43% favorable to 43% unfavorable.

- And a February Reuters/Ipsos poll showed about 4 in 10 Americans leaned toward the idea that Israel’s problems are “none of our business.”

What was particularly striking about that last one: These views were almost completely nonpartisan. It was about 4 in 10 Democrats, independents and Republicans who said Israel’s business was none of ours.

That suggests that Trump’s injection of non-interventionism in the conservative movement has caught on, even as it relates to our most significant ally in the Middle East.

But it’s more than just non-interventionism; there are also plenty of signs that even Republicans have soured on Israel.

The Quinnipiac poll showed the percentage of Republicans who sympathized more with the Israelis than Palestinians dropping from 86% in October 2023 to 64% today. (Almost all of the shift was to a neutral position, rather than to the Palestinians.)

And the Pew poll showed unfavorable views of Israel among Republicans and Republican-leaning independents rising from 27% in 2022 to 37% in March. Most remarkably, right-leaning voters under the age of 50 were about evenly split in their views of Israel.

These modest but significant shifts have come as certain corners of the MAGA movement have adopted a more skeptical view of the American alliance with Israel and cautioned against a hardline approach to Iran.

Those tensions are perhaps best exemplified by an intense and ongoing feud between Fox News host Mark Levin and his former Fox colleague, Tucker Carlson.

Carlson on Friday morning went so far as to say the United States should decouple itself from Israel altogether. He said the Trump administration should “drop Israel. Let them fight their own wars.”

Carlson said the United States not only shouldn’t send troops, but that it shouldn’t provide any funding or weapons.

Also this week, Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard used her personal X account to promote a cryptic video. She urged people to “reject this path to nuclear war” and said certain “elite warmongers” were carelessly pushing us toward it, in the knowledge that they personally had nuclear shelters that others didn’t.

It’s not clear if Gabbard was alluding to the tensions in the Middle East – as opposed to, say, the war between Russia and Ukraine. But she has long advocated a softer approach to Iran. Back in 2020, while she was still a Democrat, she called Trump’s killing of a top Iranian commander an unconstitutional “act of war.”

Republican Sen. John Kennedy of Louisiana responded this week that Gabbard should “change her meds.”

In other words, this isn’t even simple on the right anymore. Trump leads a country and a movement that are increasingly torn about the path ahead.

He has landed firmly in Israel’s corner thus far. But very difficult decisions could lie ahead.

What we know about the countries on Trump’s travel ban list, and how many people will be impacted

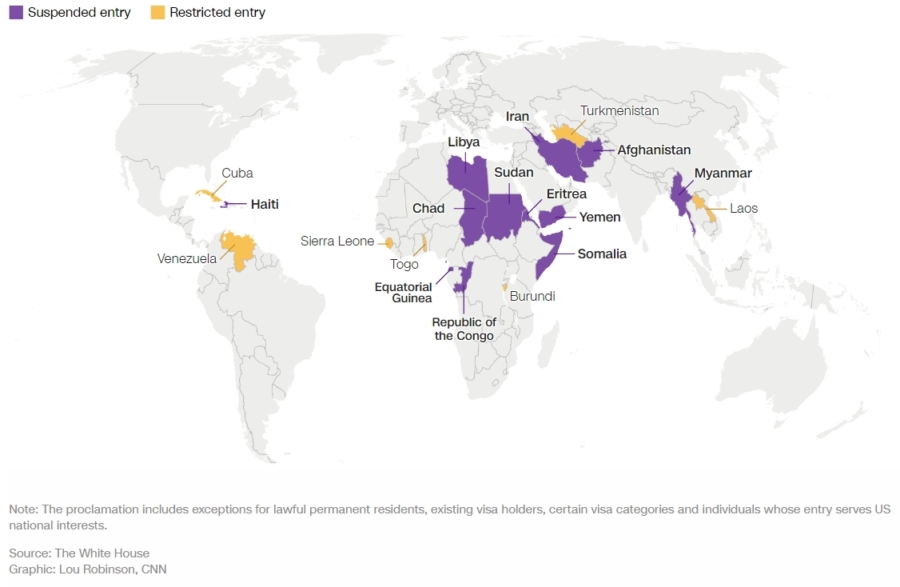

A sweeping new travel ban on citizens from a dozen nations was announced by the White House on Wednesday, reviving a defining effort from the first Trump administration to crack down on entries from specific countries.

Trump said in a video posted Wednesday that new countries could be added to the travel ban as “threats emerge around the world.”

The 12 countries targeted – plus seven more, which face partial restrictions – are mostly nations with frosty, adversarial or outwardly antagonistic relations with Washington. Many are either failed states or in the throes of repressive rule, and some are governed by groups that took control after years of US involvement in their affairs.

“Frankly, we want to keep bad people out of our country,” Trump said Thursday. “The Biden administration allowed some horrendous people, and we’re getting them out one by one, we’re not stopping until we get them out.”

For all but four of the 19 countries hit with restrictions, the administration pointed to high rates of their nationals overstaying their visas after entering the US.

Countries affected by Trump’s new travel restrictions

President Donald Trump signed a proclamation on Wednesday to ban nationals from 12 countries from entering the US. Seven other countries in this proclamation will have partial restrictions.

Visa overstays have received renewed scrutiny since the Boulder, Colorado, attack last weekend against a group campaigning in solidarity with the Israeli hostages held by Hamas in Gaza. The suspect in that attack was originally from Egypt, which was not on Wednesday’s travel ban list. He obtained a two-year work authorization that expired in March, a Homeland Security (DHS) official said.

Seven countries were included because the administration deemed they pose a “high level of risk” to the US: Burundi, Cuba, Laos, Sierra Leone, Togo, Turkmenistan and Venezuela.

The travel ban does not target existing visa or green card holders, and it also features carve-outs for some visa categories and for people whose entry serves US interests.

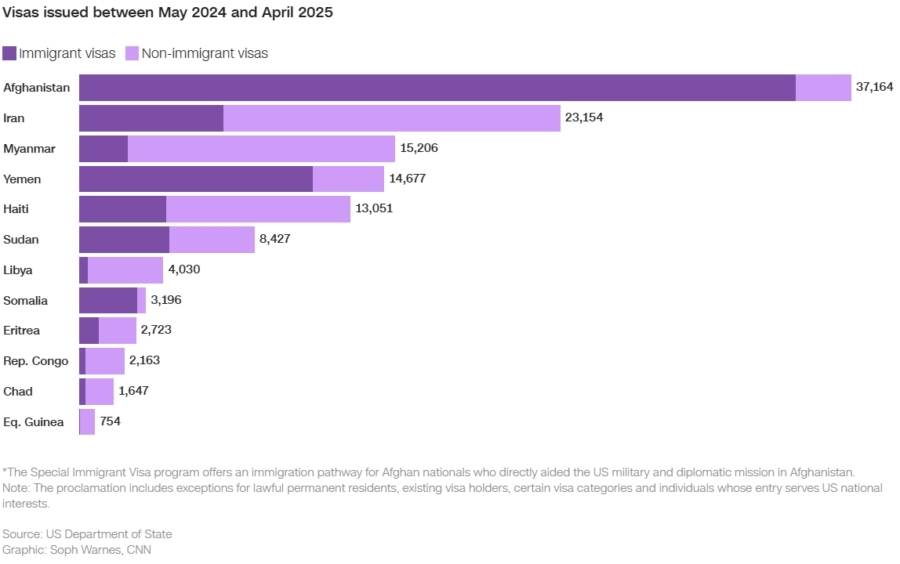

Its impact will vary greatly from country to country; some nations only receive a few hundred nonimmigrant visas per year, while others have seen hundreds of thousands of people enter the US in the past decade.

Seven African countries

Travel to the US has been fully restricted for citizens from Chad, Sudan, Libya, Eritrea, the Republic of Congo, Somalia and Equatorial Guinea. Meanwhile, a partial restriction has been imposed on nationals from Burundi, Togo and Sierra Leone.

The US does not issue a high number of visas to most of those countries – according to State Department data, only a few hundred or a few thousand people from each were granted immigrant and nonimmigrant visas in 2023.

The White House said Somalia had been identified as a “terrorist safe haven,” led by a government that lacks “command and control of its territory.” This year, the US carried out airstrikes in Somalia against ISIS and affiliated targets, in a joint counterterrorism effort with the nation.

Relations with Sudan have soured; last month, the Trump administration said it would impose sanctions on the military-led Sudanese government after finding that it used chemical weapons last year during its ongoing war with a rival military faction. The US has been unable to broker a ceasefire to end the conflict that has raged on for two years, leaving tens of thousands dead.

The White House has also had a frosty relationship with Chad, which demanded the removal of American troops from its territory last year, as well as with Eritrea, whose military the Biden administration accused in 2023 of committing war crimes during a conflict in northern Ethiopia.

Similar reprimands have been made by the US State Department against state and non-state actors in Libya, which it accused of committing crimes against humanity.

Chad had one of the highest rates of visa overstays of any country included in the ban; around half of the people admitted to the US from the central African nation overstayed their visa in the 2023 financial year, according to the DHS, though the numbers of Chadians granted such visas was relatively small. The White House said Wednesday that Chad’s overstay rate is “unacceptable and indicates a blatant disregard for U.S. immigration laws.”

The President of Chad, Mahamat Idriss Deby Itno, said on Facebook that he had told his government to “act in accordance with the principles of reciprocity” by suspending visas to citizens of the United States.

“Chad has no planes to offer, no billions of dollars to give but Chad has his dignity and pride,” he added.

Visas issued in the last year to people from countries now on the travel ban list

In the last 12 months, around 126,000 visas have been issued to nationals from countries that are now on President Trump’s travel ban list. Many Afghan immigrant visas were issued under the Special Immigrant Visa* program.

The African Union Commission said in a Thursday statement it was “concerned” about the impact of bans “on people-to-people ties, educational exchange, commercial engagement, and the broader diplomatic relations that have been carefully nurtured over decades.”

“While recognising the sovereign right of all nations to protect their borders and ensure the security of their citizens, the African Union Commission respectfully appeals to the United States to exercise this right in a manner that is balanced, evidence-based, and reflective of the long-standing partnership between the United States and Africa,” its statement read.

Afghanistan, Iran and Yemen

The ban targeted three Middle Eastern adversaries with which the US has limited or no diplomatic ties.

The US does not formally recognize the Taliban as Afghanistan’s official government. The militant group reclaimed power in 2021 amid a chaotic and deadly withdrawal of US forces under the Biden administration. Afghans who helped the US government during Washington’s two-decade involvement in the country are exempt from the ban; they fall under a Special Immigrant Visa program that has allocated more than 50,000 visas since 2009.

The Trump administration targeted Yemen’s Houthi rebels with airstrikes for several weeks earlier this year, in response to the group attacking ships and disrupting trade routes in the Red Sea. The Houthis control much of western Yemen, including the capital Sanaa.

Haiti, Cuba and Venezuela

Haiti has been in the grips of violent unrest for years. Gangs control at least 85% of its capital, Port-au-Prince, and have launched attacks in the country’s central region in recent years. The violence has left more than one million Haitians internally displaced.

Two other Latin American nations – Cuba and Venezuela – also face restrictions, though Trump stopped short of implementing a full ban. The move comes a week after the Supreme Court allowed Trump’s administration to suspend a Biden-era humanitarian parole program that let half a million people from the two countries, plus Nicaragua, temporarily live and work in the US each year.

Trump in March revoked temporary humanitarian parole for about 300,000 Cubans, amid a record number of arrivals of migrants from the Caribbean island. On Thursday, Cuba’s Foreign Minister Bruno Rodriguez Parrilla said the ban “has racist undertones” and “damages personal, professional, academic, and cultural exchanges between the two countries.”

How Trump’s travel restrictions compare to those imposed during his first term

Venezuelan Foreign Minister Yván Gil Pinto called the travel ban issued against Venezuelan nationals an “operation of hate and stigmatization,” in a statement released Thursday.

Of all the countries targeted, the new restrictions may impact Venezuelans the most. More than 55,000 people from Venezuela received nonimmigrant visas to enter the US in 2023, and nearly 800,000 Venezuelans in total were granted such visas over the preceding decade, according to the State Department.

Myanmar and Laos

The White House said both Laos and Myanmar, also known as Burma, have failed to co-operate with the US regarding the return of their nationals.

Myanmar’s ruling military junta has spent the past four years waging a brutal civil war across the Southeast Asian country, sending columns of troops on bloody rampages, torching and bombing villages, massacring residents, jailing opponents and forcing young men and women to join the army.

The junta is headed by a widely reviled army chief who overthrew the democratically elected government of Aung San Suu Kyi and installed himself as leader, and the nation was thrown into further turmoil by a devastating earthquake in March.

The US and Laos meanwhile have a complicated history, hampered by the US bombing of the country during its war in Vietnam. But relations have improved dramatically this century, and the US-Laos partnership is one of the most stable and productive of all 19 countries targeted by Wednesday’s ban.

Egypt not included

Egypt was spared inclusion in the travel ban, even though the restrictions were expedited after an Egyptian national was charged with attempted murder after the Molotov cocktail attack in Boulder, Colorado.

Egypt has long been a key US partner in the Middle East. Relations between Cairo and Washington date back to 1922, when Egypt gained independence from the United Kingdom, and have continued ever since.

According to the US embassy in Egypt, some 450 Egyptians travel to the United States annually on professional and academic exchange programs.

Trump told reporters Thursday that “Egypt has been a country that we deal with very closely. They have things under control. The countries that we have don’t have things under control.”

The Arab nation has also historically been the second biggest recipient of US military aid, following Israel. Since 1978, the US has contributed more than $50 billion in military assistance to Egypt, according to the American embassy, though some of this aid has been occasionally withheld on account of the country’s human rights record.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(999x0:1001x2)/catherine-ohara-013026-7-4b5b413a646d4f15a1fd15ac8b933811.jpg?w=1200&resize=1200,0&ssl=1)