Global health agencies announced Wednesday that generic versions of a groundbreaking injectable drug to prevent HIV will be made available from 2027 at around $40 a year in more than 100 low and middle-income countries, a move hailed as a potential gamechanger in the fight against the AIDS epidemic.

Generic versions of a groundbreaking injectable HIV-prevention drug should be available for $40 a year in more than 100 countries from 2027, Unitaid and the Gates Foundation said Wednesday.

The two organisations have entered into separate agreements with Indian pharmaceutical companies to produce cheaper generic versions of lenacapavir – a twice-yearly injection shown to reduce the risk of HIV transmission by more than 99.9 percent – for low- and middle-income countries.

Marketed under the brand name Yeztugo by California-based Gilead Sciences, lenacapavir currently costs around $28,000 a year in the United States.

Far cheaper generic versions are therefore “really critical for the scale-up of prevention of HIV”, Carmen Perez Casas, Unitaid’s strategic lead for HIV, said

“Now, with this product, we can end HIV.”

In October last year, Gilead announced that it had signed licensing deals with six generic drugmakers to produce and sell the world’s first long-acting pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in poorer countries.

Unitaid, an international health agency, said Wednesday that a partnership had been established with Dr. Reddy’s Laboratories, the Clinton Health Access Initiative (CHA) and Wits RHI to provide the drug at an annual cost of $40 per person across 120 nations starting in 2027.

“The product is going to be at the beginning manufactured in India,” Perez Casas said.

“But we also are working towards regional production in the future.”

The Gates Foundation also announced Wednesday that it had entered into a similar partnership with Indian pharmaceutical company Hetero.

“Scientific advances like lenacapavir can help us end the HIV epidemic, if they are made accessible to people who can benefit from them the most,” Trevor Mundel, head of global health at the Gates Foundation, said in a statement.

Since 2010, global efforts have helped slash the number of new HIV infections by 40 percent, but UNAIDS data shill shows 1.3 million people contracted HIV in 2024.

Pending the arrival of the new generic versions, another agreement between Gilead and the Global Fund aims to help provide affordable access to the drug in lower-income countries.

Washington confirmed earlier this month that it would honour a 2024 agreement to back that project, sparing it from President Donald Trump’s foreign aid blitz.

The initiative, which follows the US approval of Yeztugo in June, aims to deliver the first units to at least one African country by the end of this year.

Investing in Latina Women Is the Future of Ending the HIV Epidemic

Written by Cora Cartagena

About the Author:

Cora Trelles Cartagena, MPH, serves as the Manager for GLOW and NextGen: Emerging Leaders Fellowship at NMAC under the Coalition for Justice & Equality Across Movements, where she directs leadership-building public health programs designed to invest in women and youth. She is a first-generation Peruvian immigrant whose advocacy centers on health equity, language justice, and ensuring all Latine communities are seen and heard. At NMAC, Cora played a key role in launching and scaling bilingual and inclusive initiatives, including facilitating workshops in Spanish (e.g., ESCALATE en Español), and coordinating training for emerging leaders across diverse identities and geographies. Her work bridges grassroots activism, program development, and public health in pursuit of ending the HIV epidemic by centering representation, dignity, and culturally grounded leadership.

Each September, as we celebrate Latine Heritage Month, I am reminded that our stories, our culture, and our resilience are central to the fight to end the HIV epidemic. As a first-generation Peruvian immigrant and a Program Manager at NMAC, I have seen firsthand that HIV advocacy is not just about science and medicine; it is about people, culture, and justice. It is about creating spaces where all Latine women—cisgender, transgender, queer, bisexual, lesbian, straight, and pansexual—can lead with their full identities.

Through NMAC’s GLOW (Growing Leadership Opportunities for Women) and NextGen Fellowship public health programs, I have witnessed the power of investing in women one at a time. GLOW is a bilingual inclusive program where women come together to learn about HIV prevention, stigma reduction, and community organizing. Our curriculum welcomes women who identify as She and/or They (Ella/Elles) and includes Afro Latinas, undocumented immigrants, women who use substances, formerly incarcerated women, sex workers, and women of trans experience—many identities that are often excluded from mainstream public health programming.

When I think of Latinas leading the HIV movement, I think of Mila Hellfyre, a proud GLOW and NextGen young graduate and mini grant awardee, who used her project to confront HIV stigma and transphobia through storytelling and creating spaces of empowerment for transgender women in rural Puerto Rico. I also think of Lina Rodriguez, a Latine millennial leader in New York who works with Voces Latinas to support recently arrived LGBTQIA+ immigrants, helping them navigate health services and find community. I think of Natalie Sanchez, MPH, Director of UCLA Family AIDS Network, who represents us Latina women in the HIV movement as a council member in the Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS (PACHA). I also think of Silvia Valerio from TransLatina Coalition and Arianna from Arianna’s Center, two powerful women whose mentorship shapes my own advocacy. Silvia builds safety and leadership pathways for cisgender and transgender Latinas in LA, and Arianna provides HIV services and empowerment for immigrant transgender women from Florida all the way to rural Puerto Rico. They have shown me what it means to lead with meaningful action plans, compassion, and cultural humility—even when we have limited financial resources.

In these spaces, women show up fully, exploring all their identities, sharing their truths, and designing projects that meet their communities where they are. Participants do not just receive information; they create solutions focused on wellness. They design outreach campaigns, host educational events, build social media campaigns to reach women and youth, and facilitate support groups. When women are trusted directly with the tools to lead, they transform their communities.

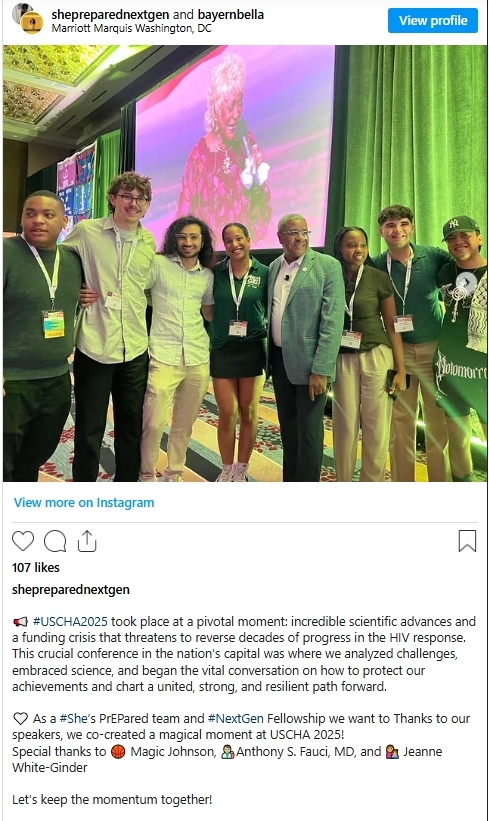

At this year’s United States Conference on HIV and AIDS, we showcased two workshops featuring short videos of projects from Los Angeles to rural Puerto Rico. These were not hypothetical case studies, but real public health initiatives born from our mini grants program, where participants received training, coaching, and seed funding to make their vision a reality. At a time when government defunding is dismantling HIV prevention and treatment infrastructure, these solutions are not just impactful—they are essential for our survival.

Community investment is not just a strategy; it is our lifeline. When we trust people with the resources to lead, they create solutions that work. Mini grants are a vote of dignity and confidence that says: your voice matters, your idea matters, and your community matters. I have seen these programs make measurable and lasting impact from Alaska and Hawaii to rural Puerto Rico. They must grow to meet the needs of our communities as public funding shrinks.

Biomedical innovation will continue advancing, but breakthroughs mean little if people cannot access or trust them. Funding trusted messengers and local leaders is how science becomes action.

This month, we also cannot ignore the fear many of our undocumented neighbors live with daily. ICE raids and racial discrimination keep too many from seeking lifesaving care. Supporting them means more than preparing workplace safety plans—it means showing up with cultural humility and rebuilding trust where it has been broken.

Above all, we must continue to trust women, immigrants, and youth to lead. We have the blueprint, we have the community, and we have the will. Together, we can end the epidemic with one person, one project, and one community at a time.

This month must remind us that undocumented people are part of every community we serve. There are more than eleven million undocumented immigrants in the United States living in fear, often invisible in our statistics. HIV does not care about immigration status, and neither should our programs.

It will take more than Spanish translations and interpretations to reach these communities. It will take representation, cultural humility, and trust. It will take a Coalition of Equity and Justice—a network that unites women, queer leaders, immigrants, and allies to fight HIV stigma, defend HIV prevention and treatment funding, and demand representation.