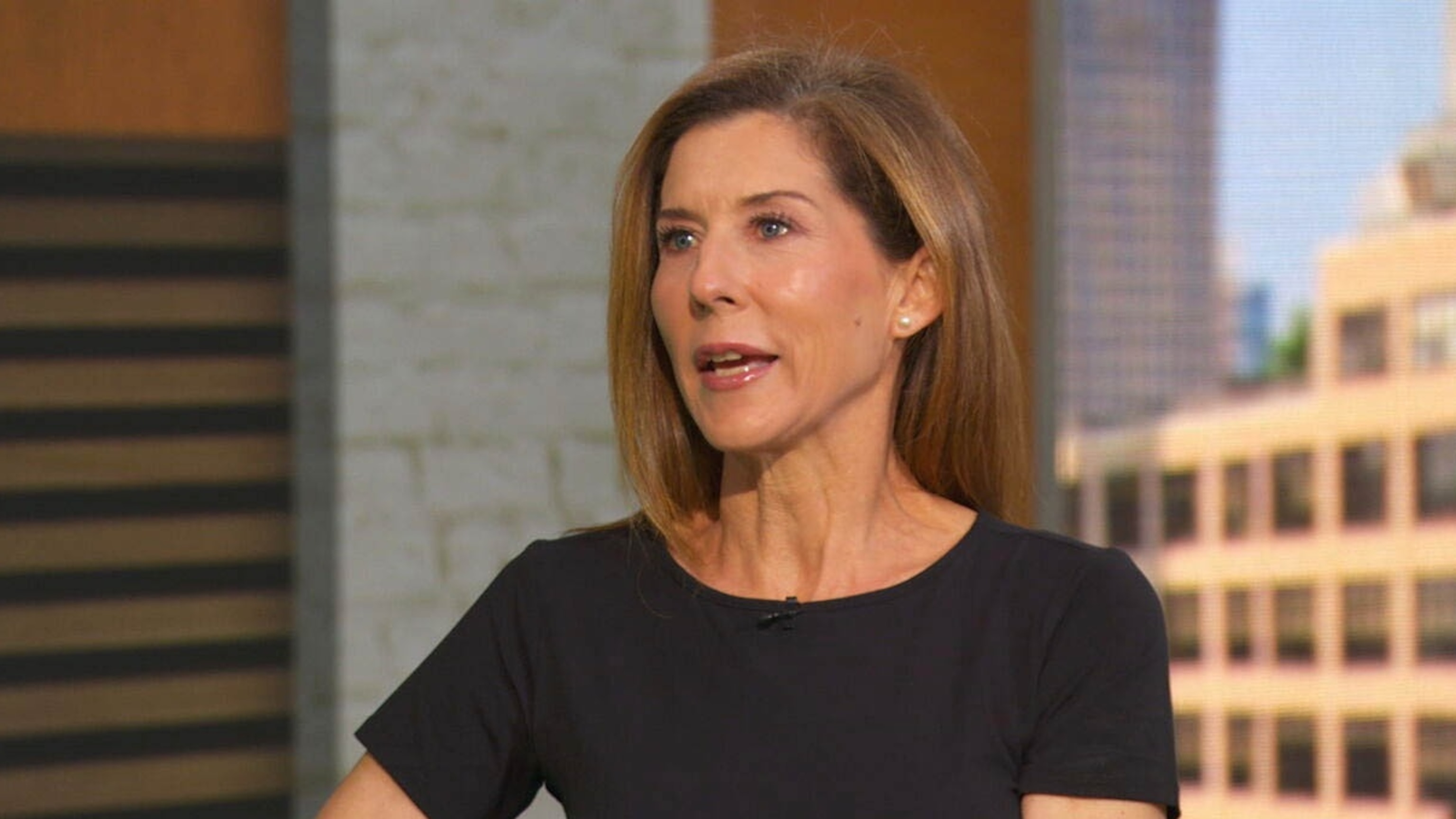

Tennis legend Monica Seles is opening up about her journey with myasthenia gravis, a neuromuscular autoimmune disease she was diagnosed with three years ago.

In a recent interview with The Associated Press, Seles, 51, said she chose to share her diagnosis ahead of the U.S. Open later this month to raise awareness about the disease, also known as MG.

Myasthenia gravis affects about 20 out of every 100,000 people in the world, according to the Cleveland Clinic.

“The actual number may be higher, as some people with mild cases may not know they have the condition,” the clinic notes. “In the United States, there are approximately 60,000 people affected by myasthenia gravis at any given time.”

Seles, whose career included nine Grand Slam titles and a place in the International Tennis Hall of Fame, said it took time to process the diagnosis.

“It took me quite some time to really absorb it, speak openly about it, because it’s a difficult one. It affects my day-to-day life quite a lot,” she told the AP.

Myasthenia gravis symptoms

Seles said she was referred to a neurologist after noticing symptoms such as double vision and weakness in her arms and legs.

“I would be playing with some kids or family members, and I would miss a ball. I was like, ‘Yeah, I see two balls.’ These are obviously symptoms that you can’t ignore,” Seles said, adding even blowing out her hair “became very difficult.”

In addition to eyes, arms and legs, myasthenia gravis can target muscles in the face and neck, according to the Cleveland Clinic, with symptoms that include:

- Muscle weakness and fatigue

- Droopy eyelids

- Blurry or double vision

- Limited facial expressions

- Difficulty speaking, swallowing or chewing

- Trouble walking

Muscles usually get weaker when someone is active and strengthen when they rest, the clinic adds.

What causes myasthenia gravis?

The autoimmune form of MG happens when the body’s immune system mistakenly attacks itself, the Cleveland Clinic says. It is unclear why this happens.

“Studies suggest that certain immune system cells in your thymus gland have trouble identifying what’s a threat to your body (like bacteria or viruses) versus healthy components,” the clinic adds.

While the disease can affect people of any age, the Mayo Clinic notes it is more common in women younger than 40 and in men older than 60.

Myasthenia gravis treatment

There is no cure for myasthenia gravis, although treatment can help with symptoms.

Treatment options include medications, thymus gland removal surgery, lifestyle changes and more, according to the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

“Some cases of myasthenia gravis may go into remission, either temporarily or permanently and muscle weakness may disappear completely,” the institute added.

Tennis Hall of Famer Monica Seles Opens Up About Myasthenia Gravis Diagnosis: ‘It’s a Difficult One’

The nine-time major tennis champion is raising awareness about the neuromuscular disease ahead of this month’s U.S. Open

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(749x0:751x2):format(webp)/monica-seles-1-081225-2815a3e6c5304b2f9cbcc70261364625.jpg)

Monica Seles is opening up about a neuromuscular disease diagnosis that has impacted her daily life “quite a lot” in recent years.

The International Tennis Hall of Famer, 51, revealed to the Associated Press that she was diagnosed three years ago with myasthenia gravis, a neuromuscular autoimmune disease that causes a person’s muscles to feel weak and quickly grow tired.

In addition to muscle weakness, according to the Mayo Clinic, myasthenia gravis can cause a person to have double vision and drooping eyelids. It can also cause problems speaking, breathing, swallowing and chewing. There is no cure for the disease.

The retired Serbian-American women’s tennis star told the AP she began noticing symptoms of the disease while playing tennis with her family and began seeing multiple balls coming toward her.

“I would be playing with some kids or family members, and I would miss a ball. I was like, ‘Yeah, I see two balls.’ These are obviously symptoms that you can’t ignore,” Seles said.

“And, for me, this is when this journey started. And it took me quite some time to really absorb it, speak openly about it, because it’s a difficult one,” she continued. “It affects my day-to-day life quite a lot.”

Seles told the outlet that routine daily tasks like doing her hair “became very difficult” to manage. The nine-time grand slam tennis champion told the AP she had never heard of the disease before she was diagnosed, inspiring her to speak up about it now ahead of the U.S. Open, which begins next week.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(749x0:751x2):format(webp)/monica-seles-3-081225-a274458e4aa64d81b66671819e482c47.jpg)

“When I got diagnosed, I was like, ‘What?!’” Seles recalled. “So this is where — I can’t emphasize enough — I wish I had somebody like me speak up about it.”

Seles is partnering with a Dutch immunology company as a primary spokesperson for its “Go for Greater” campaign to help those living with myasthenia gravis find resources to help them manage their life with the disease.

The tennis great told the AP that her diagnosis has led her to go through yet another “hard reset” in her life, equating the experience to some of her biggest career hurdles.

Seles won eight grand slam titles as a teenager and was widely regarded to be on her way to becoming one of the most accomplished tennis stars in history when she was stabbed by a fan on the court during a match in 1993, after which she stepped away from tennis for two years.

She returned to tennis in 1995 and won one more major championship, her ninth overall, before retiring for good in 2003.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(499x0:501x2):format(webp)/monica-seles-2-081225-8b83df0bf3f5489da2f98292936f1e3f.jpg)

Never miss a story — sign up for PEOPLE’s free daily newsletter to stay up-to-date on the best of what PEOPLE has to offer, from celebrity news to compelling human interest stories.

“I call my first hard reset when I came to the U.S. as a young 13-year-old [from Yugoslavia]. Didn’t speak the language [and] left my family,” Seles told the AP.

She added, “It’s a very tough time. Then, obviously, becoming a great player, it’s a reset, too, because the fame, money, the attention, changes [everything], and it’s hard as a 16-year-old to deal with all that. Then obviously my stabbing — I had to do a huge reset.”

“And then, really, being diagnosed with myasthenia gravis: another reset,” she said. “But one thing, as I tell kids that I mentor: ‘You’ve got to always adjust. That ball is bouncing, and you’ve just got to adjust.’ And that’s what I’m doing now.”

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():focal(975x333:977x335)/ariana-grande-divorce-allegations-071823-tout-230550e499194da2b254c21d35d94f2f.jpg?w=1200&resize=1200,0&ssl=1)